Magnesium for Horses: Which Form is Best?

With so much focus on magnesium in equine diets, you may be wondering what’s the best form of magnesium for horses.

There are many ‘forms’ of magnesium available and suitable to be fed as magnesium supplements. Unfortunately, at the moment there aren’t any extensive studies that look at the comparative bioavailability of these various forms of magnesium in horses.

To help us understand which forms of magnesium are best for horses, let’s first look at where and how magnesium is absorbed.

How is magnesium absorbed?

In the horse, magnesium is absorbed from the small intestine (Hintz et al 1972), with the second half of the small intestine being slightly more effective at absorbing magnesium than the first half. It is thought that very little magnesium is absorbed from the hindgut in the horse. Small intestinal absorption of magnesium is similar to that seen in humans, rats and rabbits.

Magnesium can be absorbed a few different ways. It is thought the major process via which magnesium is absorbed is simply via passive diffusion. This is a process where magnesium simply moves from an area of high concentration to an area of lower concentration, so in the case of intestinal absorption, when the concentration of magnesium in the gut is higher than in the intestinal cells the magnesium will move across membranes to enter the body. The concentration of magnesium drives absorption in this situation so the more magnesium present in the gut, the higher the concentration and therefore the more that will be absorbed.

Solvent drag, where magnesium dissolved in water in the gut is transported into the body as water is absorbed is a second route of magnesium absorption while active transport where magnesium is transported via some sort of magnesium pump that requires energy to operate and physically drag magnesium from the gut into the body is the third mechanism demonstrated in magnesium absorption. Which of these routes of absorption play the most important role in magnesium transport in horses is unknown.

What form of magnesium is easiest for horses to absorb?

It is difficult to compare the bioavailability of various forms of magnesium between studies because different experimental methods and forms or qualities of magnesium supplements are used. A relatively recent study (2005) published in the journal ‘Magnesium Research’ reported the magnesium bioavailability from 4 inorganic and 6 organic mineral salts of magnesium in rats. This was the most comprehensive study I was able to find that studied bioavailability across a broad number of forms of magnesium in a monogastric animal (albeit, a rat).

What did they find?

The results are interesting with 2 very clear points made by the authors (Coudray et al) being:

- There were no ‘major differences’ in the intestinal magnesium absorption between the 10 forms of magnesium studied.

- All ten salts, whether they were organic or inorganic were equally efficient in restoring blood magnesium levels in plasma and red blood cells in rats.

They did however report that magnesium gluconate had the highest magnesium absorption and retention rate of all the products studied. Magnesium sulphate (commonly known as Epsom salts) and magnesium carbonate had both the lowest absorption and retention rates and this was confirmed by the fact these two supplement forms also had the highest faecal magnesium excretions.

Their results are summarised in the table below (Coudray et al 2005).

| % Mg Absorption* | % Mg Retention* | |

|---|---|---|

| Magnesium Gluconate | 57 | 36 |

| Magnesium Citrate | 50 | 34 |

| Magnesium Chloride | 49 | 35 |

| Magnesium Oxide | 48 | 34 |

| Magnesium Pidolate | 48 | 32 |

| Magnesium Lactate | 48 | 27 |

| Magnesium Acetate | 47 | 30 |

| Magnesium Aspartate | 47 | 26 |

| Magnesium Carbonate | 44 | 22 |

| Magnesium Sulphate | 35 | 19 |

What does this tell us?

While this is only one study, it does serve to demonstrate, as the authors have noted, that all of these forms of magnesium are suitable and capable of restoring magnesium levels in magnesium deficient animals. It also means that blanket statements like ‘organic magnesium is more bioavailable than inorganic magnesium’ are not supported by this research as while 2 forms of organic magnesium were the most bioavailable, magnesium chloride and magnesium oxide were the 3rd and 4th most bioavailable according to this study.

Factors to consider before you choose a form of magnesium for your horse

Looking at these results only it would seem that magnesium gluconate or magnesium citrate would be the best forms of magnesium to use while magnesium chloride appears to be the most useful inorganic source of magnesium. However, there are the following factors you should consider:

- How much magnesium is in the product – all of these various forms of magnesium contain different amounts of magnesium and therefore you would need to feed different amounts to achieve the required daily intake of magnesium. If for example you wanted to feed enough of one of these ingredients to add an additional 10 g/day of magnesium to a diet you would need to feed from as little as 17 grams of magnesium oxide to a huge 186 grams of magnesium gluconate (see the table below). Feeding the products like magnesium gluconate that contain only very small amounts of magnesium quickly becomes unpractical and will become expensive.

| Form of magnesium | % Magnesium | Amount required to feed 10 g of Magnesium/day |

|---|---|---|

| Magnesium Gluconate | 5.39 | 186 |

| Magnesium Citrate | 16.2 | 62 |

| Magnesium Chloride | 11.98 | 83 |

| Magnesium Oxide | 60.3 | 17 |

| Magnesium Pidolate | 8.6 | 116 |

| Magnesium Lactate | 10 | 100 |

| Magnesium Acetate | 11.3 | 88 |

| Magnesium Aspartate | 7.49 | 134 |

| Magnesium Carbonate | 26.23 | 38 |

| Magnesium Sulphate | 9.9 | 101 |

- Palatability – some sources of magnesium like magnesium chloride are notoriously unpalatable, so despite being a good source of magnesium from a bioavailability perspective, if you can’t get your horse to eat it, it isn’t going to help much. Magnesium sulphate is also well known as an unpalatable source of magnesium.

- Cost – typically organic minerals are more expensive than inorganic minerals, so even though they might be slightly more bioavailable, they will be more expensive, even if their superior bioavailability is accounted for. For example, magnesium citrate is approximately $40/kg. To feed 5 grams per day of magnesium that is absorbed you would need to feed 62 grams of this supplement per day (based on the 50% bioavailability observed in rats). This would cost $2.48/day. Compare this to magnesium oxide at $10/kg. To feed 5 g/day of magnesium that is absorbed you would need to feed 35 grams per day which would cost 35 cents per day. So even though magnesium oxide is less bioavailable on a percent of magnesium absorbed basis, it costs less to feed the same amount of theoretically bioavailable magnesium.

- Physical availability – some of these more obscure forms of magnesium are difficult to source, so even if they appear to be a good option for supplementation if you can’t access and purchase it easily, practically it isn’t going to work for you.

It is easy to get caught up in the bioavailability of minerals and to lose sight of the bigger picture. Always remember when assessing a mineral source to look at bioavailability together with these factors discussed above.

Magnesium Oxide

In taking all of these factors into account, magnesium oxide, which has been used as a magnesium supplement for humans and animals for decades is showing itself as an attractive option. Magnesium oxide is easy to source, cheap to buy, contains a lot of magnesium per kilogram, so you don’t need to feed a lot to achieve the level of magnesium you want in the diet and it appears to be readily absorbed in the small intestine.

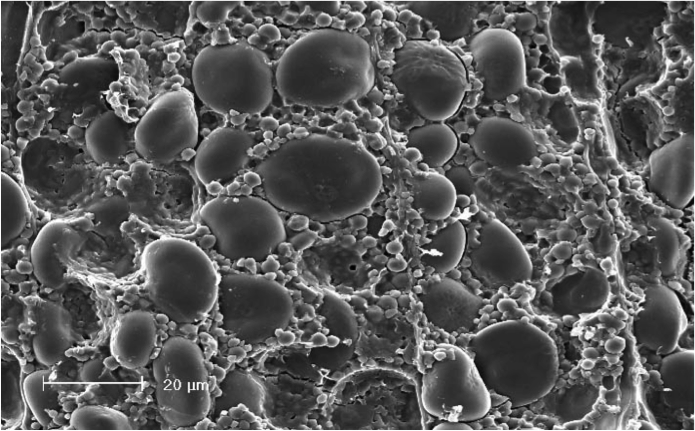

However, you do need to be careful with the type of magnesium oxide you buy and use. Magnesium oxide is made via a process of calcination where a source of magnesium like magnesite or magnesium carbonate is burned at very high temperatures to produce magnesium oxide. The way the magnesium is calcined and its final particle size affect bioavailability, with product calcined at less than 800C or with a large particle size being less bioavailable. While selecting fine particle size product is relatively simple because you can see particle size to a large degree (ie fine powders versus granular forms), it is going to be difficult to know in some cases how well the product was calcined. My best suggestion is to purchase magnesium oxide from known manufacturers that produce magnesium oxide specifically for use in animal rations. ‘Causmag’ is an example of a company that does this.

Take home message

There is actually very little known about the bioavailability of magnesium in horses. Data in rats shows us that both organic and inorganic minerals are bioavailable and that both forms are capable of restoring blood magnesium levels in magnesium-deficient animals.

However, when you take into account the amount of each supplement you would need to feed to achieve the required daily magnesium dose, the cost of the different forms of magnesium, palatability and availability factors, magnesium oxide appears to be the most practical and cost-effective magnesium supplement available for use in horse rations.

When selecting magnesium oxide for your horses, use products from reputable companies known for producing magnesium oxide for use in animal rations and select the finest particle size product you can get.

Do you have a question or comment? Do you need help with feeding?

We would love to welcome you to our FeedXL Horse Nutrition Facebook Group. Ask questions and have them answered by PhD and Masters qualified equine nutritionists and spend time with like-minded horse owners. It’s free!

Click here to join the FeedXL Horse Nutrition Facebook Group