The Importance of Fibre for Horses

Several different forms of carbohydrates form what we call ‘fibre’. These carbohydrates include cellulose, hemicelluloses and lignin. Fibre cannot be digested in a horse’s small intestine. Instead, the horse relies on the billions of bacteria that live in the hindgut to digest the fibre by fermentation. Fibre, which is also called ‘structural carbohydrate’, is essentially provided by the pasture, hay, chaff, haylage and high fibre feeds like sugarbeet and legume hulls in your horse’s diet. Fibre is the single most important component of a horse’s diet (after water) as without it, their digestive tract can’t function as it should. So why is it so important and what will happen if your horse doesn’t get enough?

Why do horses need fibre?

Fibre plays 3 very important roles in the diet of horses. These are:

- Fibre provides a source of energy/calories for horses. While the horse itself cannot ‘digest’ the carbohydrates that form fibre (because like humans they don’t have the necessary digestive enzymes to break it down in the small intestine), the horse houses billions of bacteria in its hindgut that do the job of digesting fibre for it. So, the horse provides the bacteria somewhere safe and warm to live and in return the bacteria pass on to the horse most of the energy contained in the fibre.

As well as providing the horse with energy, important vitamins like vitamin B1, biotin and vitamin K are produced during the bacterial fermentation of fibre in the hindgut. - Fibre provides the horse with ‘gut fill’. The horse’s gastrointestinal tract is an ENORMOUS organ and it needs to be kept full. The fibre in a horse’s diet is what provides the bulk to keep the gut full and healthy.

- Fibre soaks up and holds water in the gut to act as a water reserve when horses need it.

What happens if a horse doesn’t get enough fibre?

Diets that don’t provide a horse with enough fibre can cause major problems including:

- Colic – if a horse’s gastrointestinal tract is not kept full it is prone to twisting about and moving in ways that it can’t normally when it is full of fibre. Unfortunately for the horse this can lead to serious colic that can only be resolved (if the horse is lucky) by surgery.

- Diarrhoea – low fibre diets very often result in loose sloppy manure, which in-turn affects the whole dynamic of how the gut works. Horses with diarrhoea digest what fibre they do get less efficiently and they are prone to problems with dehydration and electrolyte deficiency.

- Dehydration – horses on a low fibre diet don’t have a readily available water reserve in their gut, meaning if they sweat heavily or spend an extended period of time away from water they are more prone to dehydration than a horse on a high fibre diet. Problems with diarrhoea as discussed above make this issue worse.

- Energy deficiency – horses that aren’t being fed enough fibre are also most likely not being fed enough energy (calories) so they may be losing weight or having difficulty gaining weight. The energy value of fibre is often underestimated, with forages like oaten hay or chaff often being viewed simply as a ‘filler’ when in fact they are a valuable source of energy for horses.

- Vitamin Deficiency – the bacteria that ferment fibre in the hindgut also produce several vitamins including vitamin B1, biotin and vitamin K for horses. If horses aren’t fed enough fibre the bacteria are unable to produce the amount of vitamins they normally would and a deficiency may result leading to problems like loss of appetite and poor quality hoof growth.

- Boredom – horses on low fibre diets will often have a lot of spare time to fill in during the day that ordinarily they would be spending eating. This boredom will often lead to problems like cribbing, weaving and chewing on strange objects or eating dirt.

- Gastric ulcers – the horse’s stomach is constantly releasing gastric acid and the horse relies on eating fibrous feeds to help prevent gastric ulcers. Chewing high fibre feeds like pasture or hay generates a lot of saliva which acts to buffer the gastric acid. Fibre also provides a raft in the stomach that helps to stop acid from the lower portions of the stomach from splashing up and damaging the unprotected upper portions of the stomach. Low fibre diets can’t provide this protection for horses.

- Constant hunger – because fibre is the part of the diet that provides the ‘gut fill’ a diet low in fibre will leave a horse always feeling hungry, which then causes its own set of problems including behavioural issues and even sand colic (see below).

- Sand colic – when horses are fed low fibre diets it increases the chance that sand and dirt will accumulate in their hindgut and cause colic or diarrhoea. Feeding large amounts of forage is one of the most effective ways to remove sand and dirt from the hindgut. The increased risk of sand colic in horses on low fibre diets is also partly also related to the fact that horses on low fibre diets are often hungry and if housed on dirt or sand will be going around vacuuming everything off the ground, and picking up large amounts of dirt and sand in the process.

What types of feed are high in fibre?

As you can see fibre is absolutely essential in a horse’s diet. Feeds that contain a lot of fibre include:

- All types of hay and chaff

- Most pastures (very lush green pastures are quite low in fibre)

- Haylage

- Sugarbeet pulp

- Legume hulls including soybean and lupin hulls

- Copra meal

- Seed hulls including oat and sunflower seed hulls

How much fibre does a horse need per day?

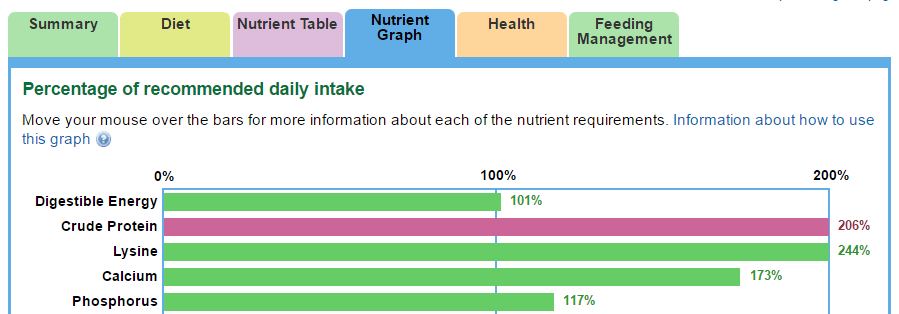

Recent recommendations are that horses should be fed a minimum of 1.5% of their bodyweight per day in forage (pasture, hay, chaff, haylage; Harris et al. 2017). This is equivalent to 1.5 kg/100 kg bodyweight or 1.5 lb per 100 lb bodyweight (which equals 7.5 kg/day for a 500 kg horse; 16.5 lb/day for an 1100 lb horse). Essentially though the more fibre you can feed in your horse’s diet the better. Use FeedXL to see if you can meet your horse’s energy requirements with high fibre feeds alone (focussing mainly on pasture and hay) and then just top up whatever vitamins and minerals are missing using a vitamin and mineral supplement.

It isn’t always possible to feed like this however and horses that are working hard need higher energy feeds like oils and cereal grains in their diet. Even for these horses it is still critically important that they are fed 1% of their bodyweight in high fibre forage.

Any of the feeds listed above can be used to provide ‘fibre’ in a horse’s diet. A second good rule of thumb to follow is to provide at least half of the fibre in your horse’s diet as long stem fibre in the form of hay or pasture. The long stem fibre takes the horse longer to eat (so keeps them happier) and also makes them chew more, which encourages more saliva production, which is important for gut health too. These long stem fibres also contain what is known as effective fibre, which is fibre that remains undigested as it passes through the gut. Effective fibre is important for allowing the horse to produce manure and shift unwanted material like sand out of the hindgut.

What other nutrients do forages provide?

High fibre forages (like pasture, hay, chaff and haylage) are a valuable source of protein. In fact for many horses these forage are more than capable of meeting 100% of their energy and protein requirements – FeedXL will show you if this is the case for your horse. Forages are particularly rich in the electrolyte mineral potassium (and sometimes contain too much of this minerals, read our FeedXL Newsletter ‘Is Pasture Affecting your Horse’s Behaviour’) and also contain good amounts of calcium, phosphorus and magnesium and varying amounts of other trace minerals (we recommend having your forages tested so you know exactly what your forage is providing your horse, then you can use FeedXL to just add what is needed). Fresh green forages are also particularly rich in vitamin A, E and K and the B-group vitamins and they are an excellent source of omega 3 fatty acids.

The final straw

Horses evolved eating a high fibre diet and fibre is still the single most important component in your horse’s diet aside from water. If your horse isn’t getting enough fibre it can be facing serious consequences including colic, dehydration, diarrhoea, ulcers, vitamin deficiency, weight loss and behavioural problems. So be sure to feed enough, it will keep your horses much healthier and far more content.

Do you have a question or comment? Do you need help with feeding?

We would love to welcome you to our FeedXL Horse Nutrition Facebook Group. Ask questions and have them answered by PhD and Masters qualified equine nutritionists and spend time with like-minded horse owners. It’s free!

Click here to join the FeedXL Horse Nutrition Facebook Group