The Gastrointestinal Tract: The Key to Feeding Your Horse

Ask any zoo-based nutritionist and they will tell you that understanding a particular animal’s gastrointestinal physiology is the key to understanding what and how to feed them. The shape, size and structure of an animal’s gut reflect what their natural diet consists of, and horses are no exception. Understanding the gastrointestinal tract is the key to feeding your horse correctly.

We know that horses are herbivores and we know that they graze for long periods each day if they have pasture available. You will also be familiar with the advice to feed ‘little and often’ and to base your horse’s diet on fibre. The reason why you should do these things lies in the way their gut is structured.

Monogastric Hindgut Fermenter

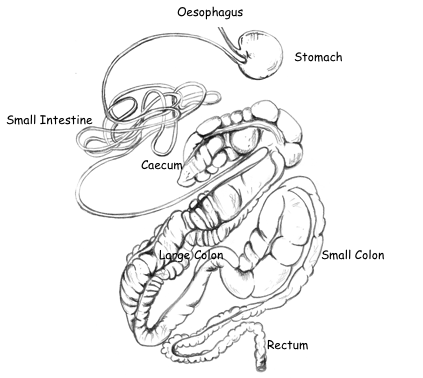

The horse can be classified as a monogastric (or single stomached) hindgut fermenter whose gastrointestinal tract consists of the mouth, stomach, small intestine, caecum, large colon, small colon and rectum (Figure 1).

The Mouth

Horses use their mobile upper lip and incisors to select and shear forage from its base or to select and pick up hay or concentrate feeds they are fed. Horses are incredibly clever with their lips and teeth and are able to carefully select feeds and forages that they either wish or do not wish to eat (often much to the frustration of their owners).

Once the feed is in the mouth it is pushed by the tongue to the molars at the back of the mouth where it is chewed extensively. During chewing, the particle size of the feed is reduced to facilitate digestion further down the gastrointestinal tract and, importantly, it is mixed with saliva. The saliva lubricates the feed, making it easy to swallow (thus preventing choke), and also provides some buffering to protect the upper regions of the stomach from the acids produced in the lower regions of the stomach. Once the feed is chewed sufficiently it is swallowed and travels down the oesophagus into the stomach.

The Stomach

The stomach of the horse is a “J” shaped organ with a capacity of approximately 5 – 15 litres meaning the stomach comprises around only 10% of the total volume of the horse’s digestive tract. The stomach has two major functions. These are:

- The storage and controlled release of feed into the small intestine; and

- The initiation of protein digestion.

The stomach of the horse is unique in comparison to other monogastrics like dogs and humans (both meal feeders) for two reasons: the first is that acidic gastric juices are constantly secreted into the stomach (dogs and humans only secrete gastric juices when they see or start to eat food); and the second is that feed tends to pass rapidly through the stomach (unlike in carnivorous monogastrics like dogs where food spends a large amount of time in the stomach).

While both of these features are well suited to the grazing horse consuming a high fibre diet, it is likely that these same design features play a role in the incidence of gastric ulcers in horses. For more information on gastric ulcers in horses, read our blog: Avoiding Equine Gastric Ulcers.

Once feed is released from the stomach it enters the small intestine.

The Small Intestine

The small intestine is where a majority of protein, fats and non-structural carbohydrates (starch and simple sugars) are digested and absorbed. The small intestine of a 500 kg (1100 lb) horse is approximately 20 to 27 meters long and has a capacity of 55 to 70 litres.

When feeds enter the small intestine they are mixed with digestive enzymes. These enzymes include proteases that digest protein, lipases that digest fats and glycanases, that digest non-structural carbohydrates. These enzymes act much like scissors, cutting the large protein, fat and carbohydrate molecules into very small pieces that can be absorbed from the small intestine into the horse’s bloodstream or lymph for transportation around the body.

The passage rate of feed through the small intestine is relatively rapid, with feed passing through the entire small intestine in as little as 45 minutes. Given that the feed can move so quickly it is very important that everything entering the small intestine is easy to digest. Horses have a natural ability to extensively digest fats and proteins, however starch from raw cereal grains is very difficult for horses to digest in the small intestine. For this reason, cereal grains must be cooked to improve its digestibility in the small intestine (read Grains for Horses: Cooked or Uncooked).

At the end of the small intestine nearly all of the fat, simple carbohydrate and a majority of the protein components should have been digested, leaving only the structural carbohydrate or fibre components to continue on and enter the hindgut.

The Hindgut

In the horse, the caecum, large colon, small colon and rectum are collectively referred to as the ‘hindgut’. The hindgut is a specialised structure the horse has developed to enable them to digest high fibre forages.

Monogastric animals do not possess the enzymes necessary to digest fibre. In order to extract the energy from fibrous feeds the horse houses billions of bacteria in its hindgut. These bacteria do possess the enzymes necessary for fibre digestion and they digest the fibre that enters the horse’s hindgut in a process known as fermentation. As bacteria ferment the fibre in the horse’s hindgut, they produce volatile fatty acids (VFAs). These VFAs are absorbed and used by the horse as a source of energy. In fact, for horses consuming pasture or hay as the major component of their diet, these VFAs are their main source of energy.

The fermentation of fibre is a lengthy process. So, the passage rate of feed through the horse’s hindgut is slowed dramatically, with feed taking from 50 hours to several days to travel from the end of the small intestine to the rectum where it is excreted as faeces, ensuring there is plenty of time for extensive fermentation to take place. This passage rate will vary however depending on how much feed a horse is eating, speeding up if large amounts of hay or pasture are consumed.

Any starch that is left undigested as it passes through the small intestine is also fermented in the hindgut. However, unlike the steady fermentation of fibre, the fermentation of starch is a rapid process. During this rapid fermentation, VFAs are produced in such large amounts that the ability of the horse to absorb them is overwhelmed. Lactic acid is also produced in large quantities and the accumulation of these acids in the horse’s hindgut causes a condition known as hindgut acidosis. Hindgut acidosis can cause serious diseases including laminitis and colic as well as loss of appetite, reduced production of vitamins, changes in behaviour and a reduced ability to digest fibre. Preventing starch from entering the hindgut must be a priority when feeding all horses. To read more about starch digestion in detail and about feeding grain, read our Grains for Horses: Cooked or Uncooked.

The hindgut’s second most important function is to reabsorb and conserve electrolytes and water that have been secreted from the body into the gastrointestinal tract during the digestion process in order to prevent dehydration and electrolyte deficiency.

It is absolutely critical to keep the hindgut healthy. For more information on the hindgut and how to keep it healthy, read our Keeping the Hindgut Healthy.

Understand the gut and you will understand how to feed

Because of the structure of the horse’s gut, we know that:

- Horses should be fed little and often (to make sure their stomach which is continuously secreting acid is never empty),

- Non-structural carbohydrates must be easy to digest in the small intestine and

- The diet should always be based on large amounts of forage to keep their hindgut full and healthy.

When putting together your horse’s diet and daily feeding routine you should always be asking yourself, what impact if any will this have on the stomach, the small intestine or the hindgut. If you find something that is not ideal, look for ways you can make it suit the horse a little better. For example, if your horse is not able to graze and you are only able to feed your horse twice a day, put its hay into a feeder like a small hole hay net so it takes much more time to eat the hay than if it was just put into an open feeder or on the ground.

Feeding to suit the structure of the gut and keeping it healthy means you will always have a horse that is healthy, on the inside and out.

Join FeedXL today and take control of your horse’s nutrition

Get EVEN MORE practical and personalised feeding guidance when you sign up to FEEDXL.

Do you have a question or comment? Do you need help with feeding?

We would love to welcome you to our FeedXL Horse Nutrition Facebook Group. Ask questions and have them answered by PhD and Masters qualified equine nutritionists and spend time with like-minded horse owners. It’s free!

Click here to join the FeedXL Horse Nutrition Facebook Group